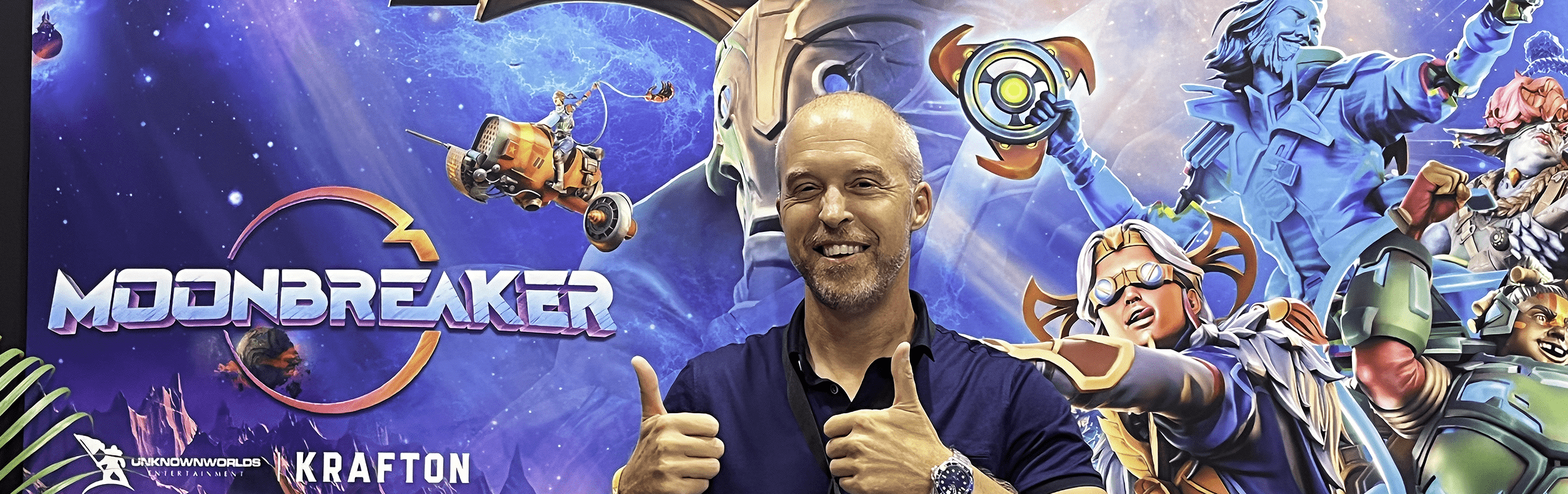

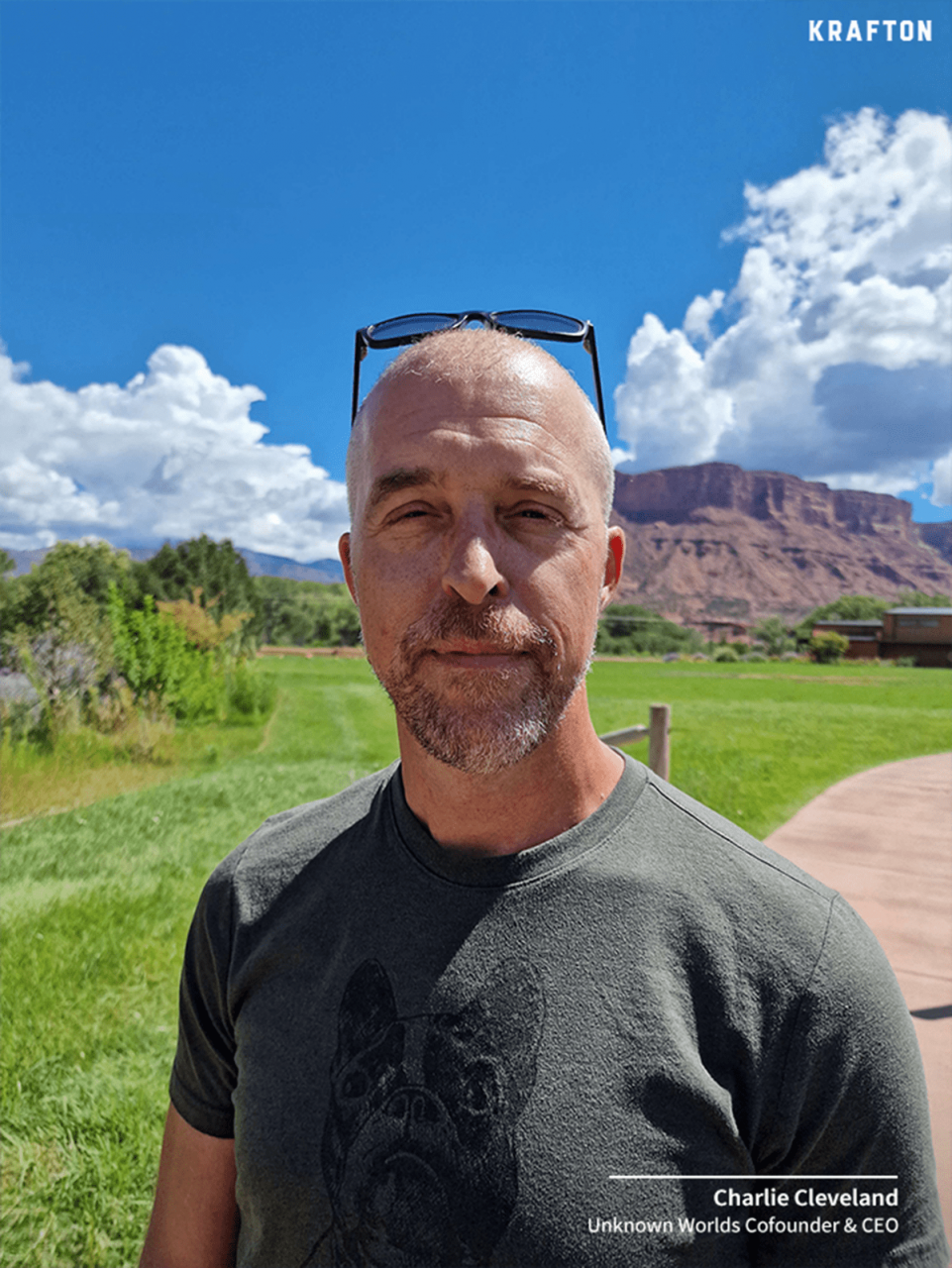

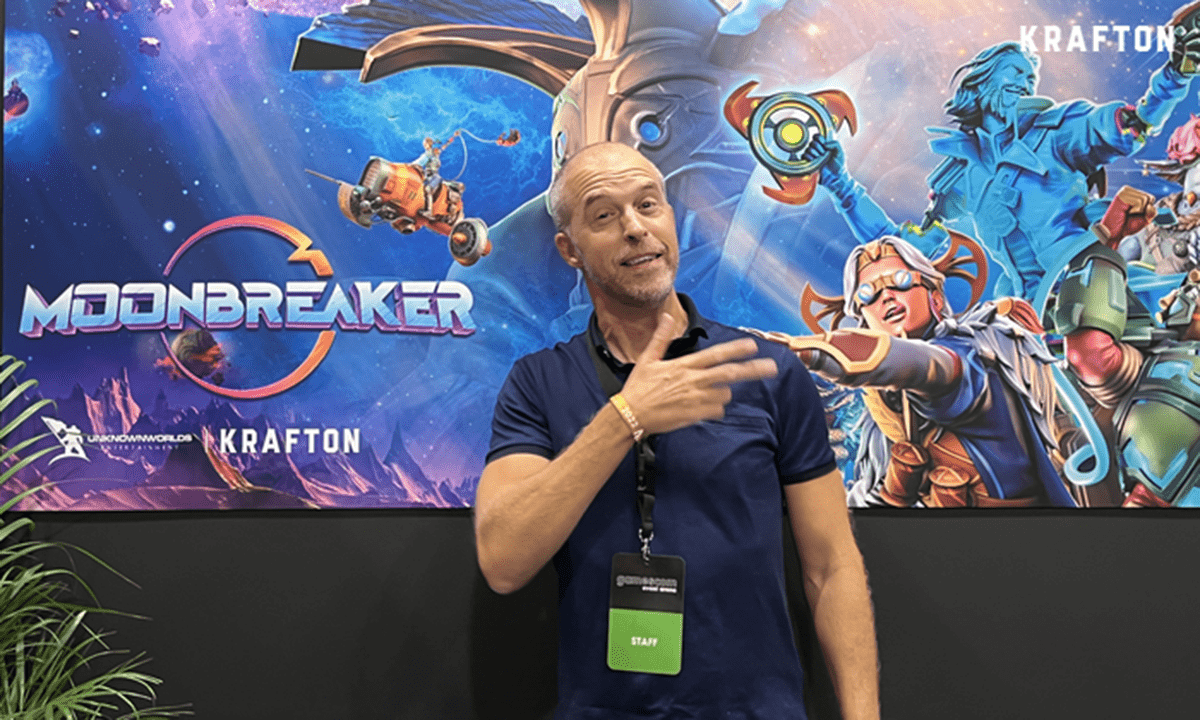

An interview with Unknown Worlds cofounder & CEO Charlie Cleveland

There are people who always seek for new challenges in life, which in turn give them thrill and a great sense of achievement. Charlie Cleveland, Unknown Worlds CEO and cofounder, is one of those challengers. At the Gamescom 2022 in Koln, Germany, he unveiled a new title, “Moonbreaker,” which looks quite different from the company’s previous games. Keep reading to learn more about his life as a game maker and the dev team’s endeavor for the new game.

Hi! Could you introduce yourself to the KRAFTON Blog readers?

I’m Charlie Cleveland. The CEO and the game design director of Unknown Worlds (UW).

Could you introduce your life as a game developer before UW?

That’s a lot of stories and it’s going to take a while. (Laughs) When I was in college, I used to take the summers off with my friends and rent a house in Vermont. Throughout the summers we locked ourselves in a room, trying to make a video game. It was around the 1990s. Back then, we didn’t have any engines, any books. I managed to find a book on game development, which was of art. I don’t remember it clearly, but I think it was “Zen of Graphics Programming” by Michael Abrash. My friends and I had to learn how to do everything by ourselves. All the rendering, drawing pixels on the screen, drawing lines, triangles and all that stuff.

For the first couple of summers, we completely failed at making a game. Most of my friends just went out, drank coffee, and played chess. And I was sitting in the room by myself, trying to learn how to make a game. And after we had failed at the end of the third summer, one of my friends and I stayed late for another two extra months. We trimmed down the idea of making a 3D game that we had just screwed to a 2D side-scroll game. We were thinking of making a copy of “Star Control II,” which was my favorite at that time. What we made was basically a 2D side-scrolling underwater aquarium game. It was about clay toys in a fish tank. We did it like animation work. We used a digital camera to photograph the toys in different poses just like they do in animation.

More importantly, we made a game that we liked to play ourselves. And I was completely thrilled. I’ll never forget the moment that I first played that game. I sat down and played against my friend. Like this moment, whenever I’m developing a game, I suddenly go into the play mode. It’s like I’m trying to win the game. So, it was the moment when the magical transition to where I am now happened. I still remember how much I was excited about the loop of going back and forth, making a game, and then playing it to see how each game turns out because they’re so different.

My first job in the game industry was in a company that did simulation driving games, which I didn’t like at all. But I learned much about game programming there and that got me onto my next job. At that point, I was ready to make my own games again. And that’s when I started working on “Natural Selection” as the mod for Half-Life.

“More importantly, we made a game that we liked to play ourselves.

And I was completely thrilled.”

Speaking of which, what made you start on UW?

I was working on Natural Selection, marines versus aliens, with Cory Strader who is now our art director at UW. At that time, Cory and I was working together at a company called Stainless Steel Studios, making what is called Empire Earth, which was one of the first 3D real-time strategy games. We were working on Natural Selection in our spare time. After a while, I left the company and devoted all my time trying to make the best game possible. I barely left my room and I’m not exaggerating. I left my room only once a week in my memory. I was completely obsessed. I was watching aliens every day to work on this game and posting update online. And this is how we got started with the early access mindset. Back in 2001, I believe it was, I was posting Cory’s texture artworks on a forum and saying, ‘Hey guys, I want to make this game and here’s the description of how to make levels for it using the Half-Life editor. My colleague made these amazing textures. Who can help?’ And thanks to that, we got people making levels for this non-existent game. We put the levels they made in the game and continued working on, making particle systems, released those and then people crafted atmospheric sci-fi particle effects for us. This was a virtuous cycle of promotion, team acquisition and game development all going together. And that culminated in the release of the game on Halloween 2002. We had around 300,000 people played the game, and I was so excited.

At that time, I wasn’t making any money out of it, and I just spent all my money to make that mod. To knew I had to make a company to continue making games. I put up a donation page for people to help subsidize the game. We called it the constellation program. Players could PayPal us or send us an actual 20-dollar bill in the mail along their Steam ID. And if they did, we would give them in-game status to show the whole community that they supported the game. The program attracted about 18,000 dollars a year and that was just enough money to survive.

And then I moved to San Francisco where I knew I could find investors and start my new game developer’s life professionally. And then I went on, very slowly and painstakingly, finding investors, convincing UW Chief Technical Director Max McGuire to join, convincing Cory to join officially. We made some middleware and a downloadable Sudoku game, all to subsidize. And then that eventually got us to the point where we wrote an engine, got investors, finished “Natural Selection 2” which took 10 years to release Steam. This made enough money to let us start making “Subnautica,” which was released after three years.

“This was a virtuous cycle of promotion, team acquisition,

and game development all going together.

What is your biggest driving force that kept you staying in game development?

It’s just the love of the game and the process of making games. I didn’t really need a lot of encouragement. It’s just my happy spot, my happy space.

Except for the one you’ve made by yourself, what’s your favorite games and why?

“StarCraft.” I don’t know if I had to say the first StarCraft or the second, but I think it’s the first one. Why? It’s just a masterpiece of game design. I learned so much about game design from studying that game. How resource economies work, how to think about asymmetric factions how skills should factor into. Like attention overload, skill curves, everything from letting players play the game, get them easily into the game but also having an infinite skill ceiling, and how to integrate narrative with game design and so on.

What’s your biggest source of inspiration that keeps you designing new creative games?

I think I don’t really have a specific source of inspiration. I just get excited when I’m relaxing or on vacation. New game ideas are appearing in my mind any time and I just like to work on them. And sometimes I have a certain idea when I get bitten by a bug. I just become obsessed with it. And then I just keep on working until it’s going to suck for a very long time. Hopefully at some point it’s going to be good.

How would you describe your UW colleagues, especially the Moonbreaker dev team?

Our team is comprised of new employees, recently joined to the company as well as some folks from the Subnautica team. And I’d say it’s an extremely high performing and creative team. We’re experts in our different domains. Everyone wants to elevate their craft to the top level, and we all push each other to do that. I think our team itself is where our ideas come from. Although I’m leading game design here, I don’t think the ideas are not coming from just me or anything. That’s a really positive attribute. Anyone feels like they could improve the game, I hope.

UW has been a fully distributed company even before the pandemic. How did you come up with such an idea? And how has this idea worked in all those years?

It was necessity because even with the first Natural Selection, it was just me in my apartment and I had no money. I couldn’t hire people and couldn’t afford an office. I just had to post updates online and ask people to help. So, I didn’t have a choice about where those people lived. So, that’s how it started. Although it was never a decision back then, we’ve been doing it for 20 years.

Is there a reason why UW advocates for open development?

Yes, there’re many reasons. One, its great publicity. Because our fans love it when we talk about this stuff. Two, it makes way better games because our fans can contribute ideas and show us our blind spots. Often when you’re working on a game for a long time, you’re missing stuff. So, you need outside perspective. Three, it’s just a lot nicer to be able to speak to people freely, instead of having to think like, ‘Can I say this? Can I say that?’ or having some schedule where you’re not allowed to say things? I think it’s just a very natural human way of being. That’s why I like it.

What was the most satisfying moment working at UW?

It was probably when I was releasing Natural Selection 2. The very night when we released it. Because it took 10 years to get there, we almost went out of business so many times in the process. And it was such a labor of love. I was just so happy to have that game out. Also, it was the first night that we met many of our teammates in person. We spend some of our last budget to get people to the office, so that we could celebrate all together. And then it hit No. 1 on Steam like immediately, which was just unbelievable. At that time, there’re fewer games on Steam so it was relatively easier to hit number one. But it just felt so validating. It felt validating to finish it. I felt validating to not care how I did. I mean, I did care but ultimately, I just wanted to have finished it and I was proud of it. And it was wonderful to see everyone to be celebrating that all together.

I heard you’re a board game designer in your spare time. Could you tell us how you do that?

I’ve always wanted to make board games. I’ve always wanted to do video games, board games and film scripts. So, this is a goal of mine. I did and am still doing video games. Likewise, I did board games, too. Basically, I just challenged myself to make a board game. I was in Italy one summer night and I just had nothing to do. And then the idea of board game that I’ve had came into my mind and I was like I had to do it. So, I told my friends that I’m going to have a playable board game that we’re going to play tomorrow. And I made that challenge and 90 minutes later, I made the world’s worst board game! (Laughs) And then we played it the next day and I was so excited. It was like the aquarium fighter that I made long before. I made probably 30 to 40 different versions of it. I probably got a master’s or a Ph. D in board game design just by pure experienced! (Laughs) I wasted a lot of time. But that eventually became “Vampire: The Masquerade – Vendetta.” I released it a couple of years ago, right at the beginning of the pandemic unfortunately. Also, I got to collaborate on that with Bruno Faidutti who was a very famous and excellent board game designer. He taught me a ton. So, it was the only board game I finished and released. I’ve got a couple more brewing. But I’m not currently working on these since I’ve been so busy with Moonbreaker.

Okay then, let’s talk about your newest game, Moonbreaker. Could you introduce the game to our readers?

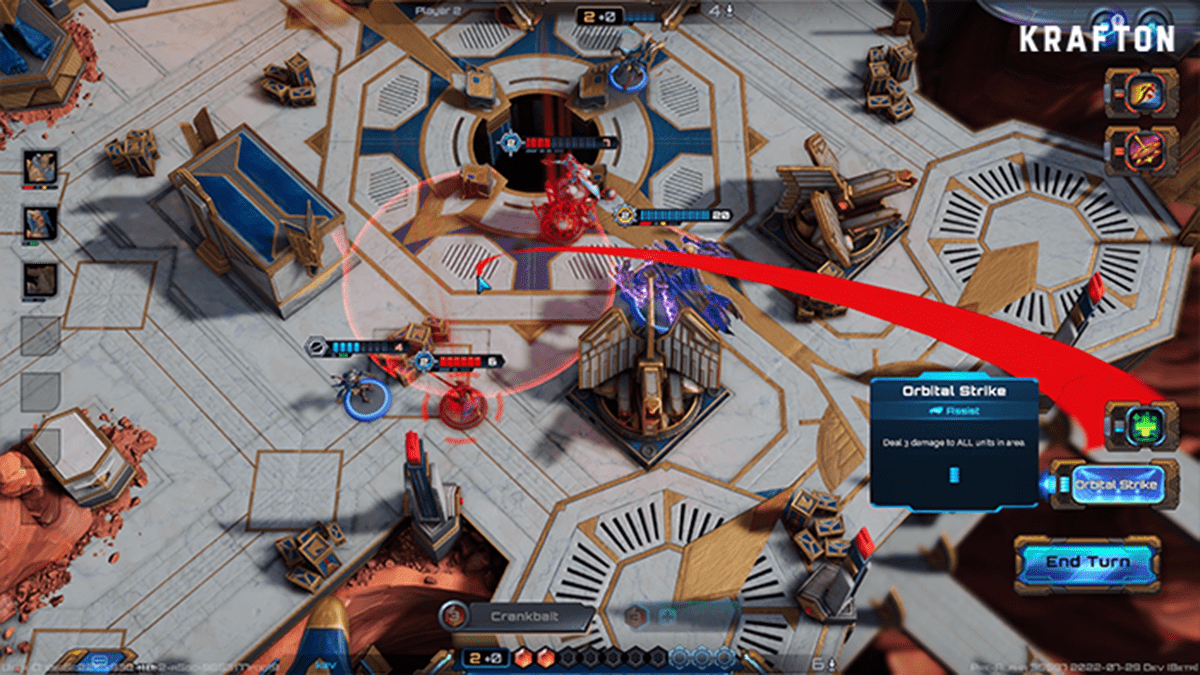

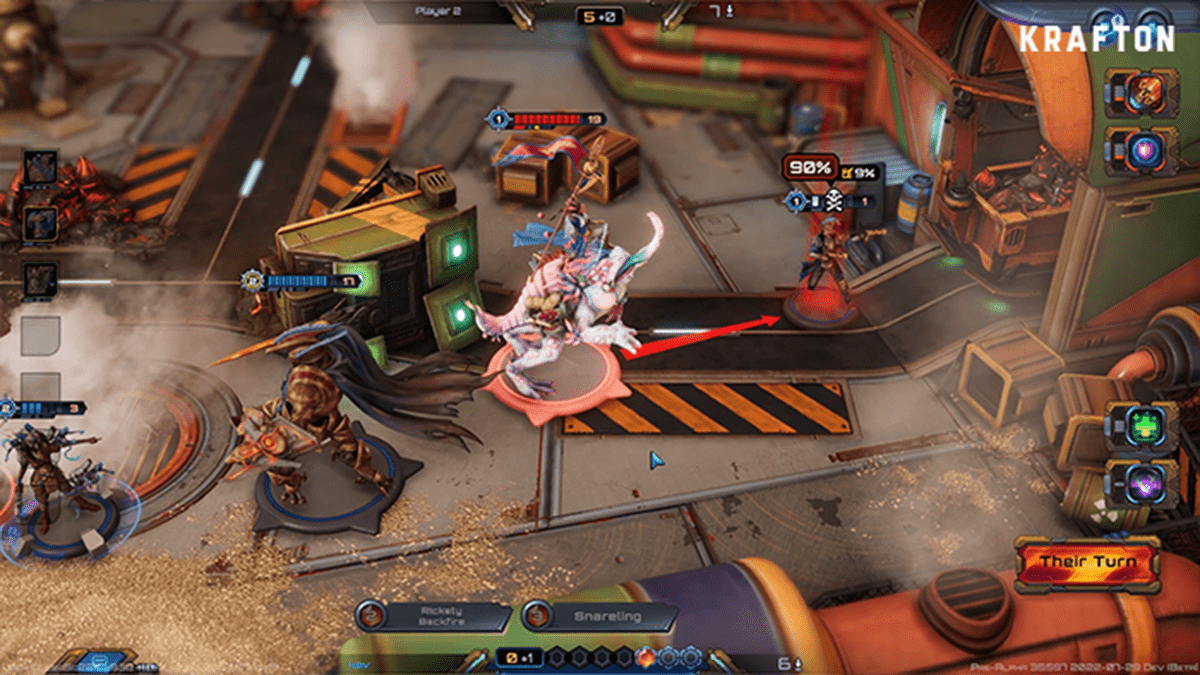

Moonbreaker is a turn-based tactical strategy game that fully simulates the tabletop experience. So, imagine a tabletop, a real-life tabletop miniatures game but made accessible streamlined and fully digital. So, this is a game where you’re pushing miniatures around on a digital table and you’re painting them and they’re coming to life in your mind through stories and through massive world lore. And the richness comes from the different abilities from the units themselves.

Moonbreaker looks quite different from UW’s previous titles. What made you and the developers decide to make a new challenge on a totally different genre?

We heard the same thing when we went from first-person shooter / real-time strategy Natural Selection 2 to single player nonviolent survival game Subnautica. So, we’re no strangers to changing genre. I think we just like to do different things. So, we get bored if we’re just doing the same thing over and over.

So, did your love for tabletop games have any influence on designing Moonbreaker?

That’s good question. I didn’t play a lot of miniature games as kid. I remember painting a lot of miniatures. I did play a little Warhammer and some Mech Warrior: Dark Age. I was more into collectable card games (CCGs), but I remember painting a lot of miniatures with my friends. I love tabletop. Obsessed with it. So, I can’t say there’s not way that it didn’t have a big influence.

Among video games, I’d say studying Magic: The Gathering and Hearthstone has helped a lot with Moonbreaker. But I got more inspiration from tabletop games, and tabletop-inspired video games.

For those who love collecting and decorating miniatures as a hobby, Moonbreaker’s painting feature would be an attractive point. Can you elaborate on it?

We wanted to bring the entire hobby aspect of tabletop miniatures to digital. It’s not just the game. It also includes the hobby aspect and the storytelling. Those other two pieces are key in the tabletop hobby. So, I would say maybe half your time in Moonbreaker will just be painting for the average player. Maybe half the time is playing. Maybe 10 percent of your time can be listening to audio dramas and lore. But that doesn’t add up to a hundred. It’s hundred ten percent. But, yeah, we want to bring and preserve the hobby aspect. There’s a community aspect of painting.

How was the collaboration with Brandon Sanderson on Moonbreaker’s lore?

It’s been amazing. Brandon is a true expert in his craft and is also a game designer. He thinks like a game designer for sure. You can see that with how he designs his magic systems in his Cosmere works and in other books. So, it was actually pretty effortless to make that work. He totally understood the needs of this game. And any time there was any discrepancy between the two, he just didn’t mind it all. Either just seeding something to the needs of the game or we would just create a new, we would just create a solution to a problem. Because he understood the problem well enough. And that guy also is a machine. I don’t even know when he sleeps.

And for those who lack experience with miniatures or tabletop games, do you have any tips to enjoy Moonbreaker to the fullest?

You don’t need miniatures or tabletop experience to play the game. But I mean strategy game experience would certainly help. I mean it’s just a piece of gameplay advice. Think about how your units are positioned. That’s the most important part of the game. And think about how you can use your units to give soft cover to your other units. And think very carefully about the order of your moves. Ideally if you’re a very disciplined person, which I am not particularly, you can think about your entire set of moves and actions exactly before you take the first one. So, if you’re playing Moonbreaker super well, you’ll plan the entire thing. You want to stay on your side of the board for 30 seconds to plan it all out and then execute it as fast as possible. And it feels like you’re solving a puzzle because sometimes you’ll have no idea what to do. But, if once sometimes you find just the right move and you feels it like a key that opens the lock. It’s a very specific feeling. But remember that in every turn the puzzle is completely different!

*Moonbreaker Official Website: https://moonbreaker.com/

*Moonbreaker Steam Store Page: https://store.steampowered.com/app/845890/Moonbreaker/